'The Discarded Image' Commentary - Part One: A Road Map to the Medieval Mind

A Survey of C.S. Lewis's Final Book

Recently I revisited C.S. Lewis’s invaluable book The Discarded Image, which is the good professor’s roadmap to the Medieval mind (also, as I’ve recently learned, his last completed book, published shortly after his death). This is the sort of book that anyone who aspires to writing or teaching or even just reading above a purely surface level ought to make themselves familiar with. It’s also the sort that almost can’t help but spark a thousand new ideas in its readers.

With that in mind, I’ve decided to attempt a kind of casual commentary on it, sharing some of the ideas that it’s generated in me. This is done largely in the absence of any further research, as I feel like embarking on a research trip could easily turn into a bottomless pit. It is offered in the hopes that my readers (assuming I still have any) will find it interesting, entertaining, and be encouraged to seek out and read the book for themselves.

First of all, a small warning to those who want to read along: Lewis has a reputation as an easy read, famous for being able to make difficult ideas accessible. This, however, is a different side to him. This is Lewis the professor, not the popularizer or the children’s author. The Discarded Image was written as a primer for university students studying Medieval and Renaissance Literature, and while it still has something of his breezy, conversational style, it is a complex and sometimes challenging work that expects the reader to be already familiar with the works of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Dante, and a host of their lesser satellites (at one point he passes over discussing Ptolemy’s Almagest on the grounds that, being available in a French translation, his students should be able to familiarize themselves with it). Anyone approaching it expecting the same kind of accessibility as some of his more famous works (e.g. Mere Christianity) will find himself plunged into a bewildering mass of arcane citations and fine technical distinctions.

That isn’t to say the book is inaccessible to non-scholars (after all, I wouldn’t call myself one), only that it will demand a good deal more of the reader than one only familiar with the author’s more famous works may be expecting.

Lewis starts off with a lengthy illustration of a key and oft-neglected fact of the Medieval mind:

Medieval man shared many ignorances with the savage, and some of his beliefs may suggest savage parallels to an anthropologist. But he had not usually reached these beliefs by the same route as the savage.

(Note: To be clear to anyone who doesn’t know, Lewis uses the term ‘savage’ in its old, nonperjorative sense of ‘a people in a simple or primitive state of social development’)

Savage beliefs are thought to be the spontaneous response of a human group to its environment, a response made principally by the imagination. They exemplify what some writers call pre-logical thinking. They are closely bound up with the communal life of the group. What we should describe as political, military, and agricultural operations are not easily distinguished from rituals; ritual and belief beget and support one another. The most characteristically medieval thought does not arise in that way.

He then proceeds to give two examples of Medieval ideas – first the notion of a intermediary class of ‘spirits’, some good, some bad, inhabiting the air, second the distinction between ‘nature’ and ‘sky’, with the Moon as its boundary – and traces them to their classical sources, before concluding:

What both examples illustrate is the overwhelmingly bookish or clerkly character of medieval culture. When we speak of the Middle Ages as the ages of authority we are usually thinking about the authority of the Church. But they were the age not only of her authority, but of authorities. If their culture is regarded as a response to environment, then the elements in that environment to which it responded most vigorously were manuscripts. Every writer, if he possibly can, bases himself on an earlier writer, follows an auctour: preferably a Latin one. This is one of the things that differentiate the period almost equally from savagery and from our modern civilisation. In a savage community you absorb your culture, in part unconsciously, from participation in the immemorial pattern of behaviour, and in part by word of mouth, from the old men of the tribe. In our own society most knowledge depends, in the last resort, on observation. But the Middle Ages depended predominantly on books. (emph. mine) Though literacy was of course far rarer then than now, reading was in one way a more important ingredient of the total culture.

This is the key point, and will be the central theme of the book: that Medieval man is extremely ‘bookish’, drawing his framework and understanding of the cosmos primarily from the things he has read, especially the works of antiquity. That is to say, the medievals, though not a broadly literate society, were enormously influenced by what they read. A medieval author would hardly ever dream of ‘making something up;’ he would instead draw from and perhaps prune and ‘correct’ some great author of the past. Nearly every facet of the medieval cosmos can be traced back to some classical or near-classical work, set into an overall Christian frame.

Moreover, once believing in the ‘airy spirits’, the Medieval proceeds to ask questions such as “why is it appropriate for the air to be so populated?” and to give a plausible and logical (if not necessarily true) answer in the principle of plenitude, which says that all regions of creation ought to be populated with suitable beings so that nothing shall go to waste (we’ll come back to that at a later chapter).

The modern stereotype (flattering, as most such are, to modernity) thinks of the Medieval mind as primitive, illogical, credulous. Only the third is true, to an extent. On the contrary, the characteristic of the medieval mind is that it is logical and orderly to a fault, and their credulousness is largely a matter of their reluctance to simply reject anything written by an ‘author of renown’ (which also dispenses of another, though less common stereotype: the Christian who blindly rejects any non-Christian sources. This one, as Lewis will point out later, is not completely false, but is not at all the norm).

For this is the real character of the (educated) medieval mind, according to Lewis: “At his most characteristic, medieval man was not a dreamer nor a wanderer. He was an organiser, a codifier, a builder of systems.”Lewis quips half-seriously that the modern invention the medievals would be most interested in is the card index. Speaking from a near-century onward, we can suggest an even greater irony: that the medieval scholar, in his mental framework, probably resembled nothing so much as a skilled software engineer!

Indeed, during my own brief time at the trade, I noticed that there was something of a philosophical trend to a lot of the concepts. I don’t mean just the logic of if-than, go-to and so on. I mean things like classes expressed in objects – grouping particular sets of code to do specific tasks (which recalls the notion of genera, species, and individuals) – or interfaces – which are classes that cannot be directly called, but can be linked with other classes (one might say, like accidents in the Aristotelian sense). I think once he got the hang of the machine, the average medieval clerk would probably have found programming incredibly intuitive in many ways.

The medieval mind, according to Lewis, loved nothing better than “Sorting out and tidying up,” having “a place for everything, and everything in its place.” Not only does everything from every book have to be worked into the model of the cosmos, but it all has to fit together.

Quoth Lewis:

[The medievals] inherit a very heterogeneous collection of books; Judaic, Pagan, Platonic, Aristotelian, Stoical, Primitive Christian, Patristic. Or (by a different classification) chronicles, epic poems, sermons, visions, philosophical treatises, satires. Obviously their auctours will contradict one another. They will seem to do so even more often if you ignore the distinction of kinds and take your science impartially from the poets and philosophers; and this the medievals very often did in fact though they would have been well able to point out, in theory, that poets feigned. If, under these conditions, one has also a great reluctance flatly to disbelieve anything in a book, then here there is obviously both an urgent need and a glorious opportunity for sorting out and tidying up. All the apparent contradictions must be harmonised. A Model must be built which will get everything in without a clash; and it can do this only by becoming intricate, by mediating its unity through a great, and finely ordered, multiplicity.

The result is a twisting, complex, crowded, yet elegant framework that tries to fit in everything that was ever reported by Pagan, Christian, and Heretical writers alike about the nature and content of the world. Their modern heirs, one might say, are those obsessive fans of Star Wars or Star Trek who try to work out theories to account for every continuity error, contradiction, and plot-hole across the entire series, down to explaining why parts of the Enterprise look suspiciously like under-funded soundstages.

Of course, the Medieval Model of the universe is a rather more elegant and beautiful thing than those fan theories (impressive though some of them undoubtedly are). Lewis describes it as one of the supreme works of the medieval era, sitting beside the Summa Theologica and the Divine Comedy.

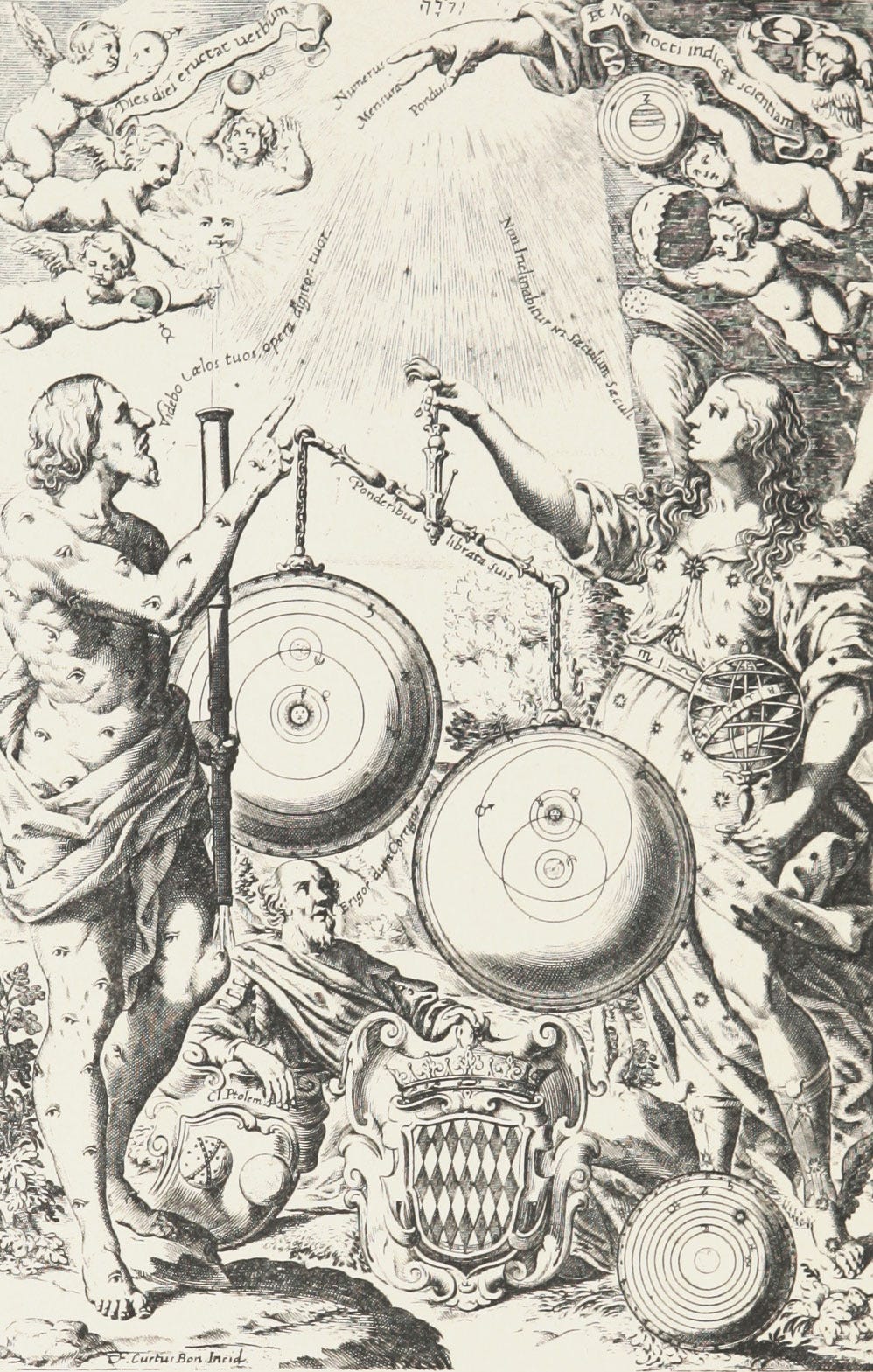

In the process, Lewis points out something I’ve often noticed, though he doesn’t expand upon it as much as I would have liked (that not being his purpose). The two sublime works just mentioned are each at once intensely crowded and intensely ordered: they are “vast in scale, but limited and intelligible.” Every corner is filled, but nothing is filled at random and nothing is done without purpose. The same taste is expressed in the soaring, intricately carved cathedrals, with saints crowding around every door and florets covering every flying buttress and demons carved into the drainpipes. It’s also found in Medieval and Renaissance illustrations, which, not content to depict their subjects, fill in every corner of the canvas with heraldry, decorations, and symbolic drawings.

Indeed, one might say that this densely crowded order is expressed in the whole of medieval society, with its tapestry of overlapping loyalties, communities, and authorities, each with its own laws, hierarchies, saints, and feasts corresponding to every class, craft, and trade under Heaven (and several under Hell, as even thieves and prostitutes had their particular guilds, saints, and devotions). It is found in the liturgical year with its intricate pattern of feasts and fasts, down to proper prayers for every hour of every day.

This, I would say, is a distinctly Catholic taste: the desire for God to fill the universe and for everything to be seen in its right relation to Him and to everything else, to fill every available space not just with material, but with meaningful material. This reflects their idea of creation itself, as expressed in the aforementioned principle of plenitude, as well as the idea that everything is created by God, who “does not create to no purpose,” as Lewis’s fellow professor wrote (and whose own work itself illustrates something like this ‘densely crowded order’), and thus nothing on earth can be dismissed as unimportant or ‘merely’ practical.

Generally speaking, this medieval / Catholic style stands in stark contrast with the modern modern style of art, which is content to leave huge swaths of the canvas blank or covered over in one colour in order to better highlight the few small images that really matter.

Compare:

One could speculate on how this reflects modern thought, which is continually trying to simplify reality, to stretch each hypothesis to the breaking point and beyond so as to cover as much of the universe as possible, but that’s beyond the scope of either Lewis’s work or my own.

In any case, Lewis closes the first chapter by submitting the medieval model for our consideration, not only as necessary background for understanding medieval literature, but as a sublime work of art in itself. One would be hard-pressed, I think, not to agree with him after reading the book.