The Last Harvest

In the waning days of the solar system, one stubborn old farmer continues to plow the Rings of Saturn under the dying Sun.

Senek was awake at four in the morning as usual, without so much as an alarm clock. After nearly eighty years of practice, he just naturally got up before the crack of dawn.

Not that dawn meant much this far from the Sun.

The old man rose, stretched his arthritic limbs, and made his usual morning devotions before stepping into his jumpsuit and sitting down to a breakfast of porridge and bacon while unfolding his ancient paper and trying to bring up a news report. There wasn’t much of a signal these days; at least, not in the old planets, and the holographic-projection paper, like its owner, had seen better days. Most of the news came in from the new systems – so they were still called, though mankind had occupied some of them for thousands of years – and was about the usual politics, crime, war, the rest; all completely irrelevant to an old Ring Farmer dwelling lightyears from any of it.

Of course, he hadn’t much cared about the news even when it had been about things closer to home. Reading the paper over breakfast was just a habit.

The only item that remotely interested him was a piece titled Why They Stay: Life in the Shadow of a Supernova. It was an interview with some of the people who had elected to remain on Earth years after everyone else had evacuated.

“We believe that the Earth is our home. It was where humanity first arose, it was for many thousands of years the only world we knew, and for tens of thousands more it was the heart of our civilization. For most of us, it’s still the only home we’ve ever known. If this is to be its final years, we would rather stay with it until the end.”

Senek’s smooth, thin skin crinkled in thought. He supposed some folk were sentimental like that. It was an interesting idea: sort of like sitting by a loved one until their last breath…

“But that ain’t why I stayed,” he said aloud. “I stayed ‘cause I have a job to do.”

Silence answered him. But he knew what would have been said.

“I’ve never missed a day of work in my life. You think I’m gonna start now just because some big-brains say the world might end today? Besides, that old Sun’s outlived plenty of men before me. Odds are he’ll still be going by the time I kick off.”

There was no one else there. Aria was up on the hill, under a stone: not in the kitchen where she belonged. Talking to her and answering what she would have said was another old habit, one he had made no effort to curb for six years.

He rose, drained the rest of his coffee, and headed out to the barn. It was harvest time and he had a lot of work to do.

The old combine ship had been acting up last night during the final radiating run; front thrusters weren’t responding. He couldn’t have that during harvest time. Senek fired up his mechbot and set it to work removing the panel. Like everything he owned, the robot was old: old and falling apart. But it got the big, heavy panel off the side of the ship after only one or two malfunctions and Senek was able to look over the problem. Just as he suspected, one of the compression lines was frayed. That meant most of the energy was burning off inside the ship and going into the exhaust ports instead of firing out the thruster like it was supposed to.

He searched through his racks, but couldn’t find a replacement. Of course not; there was hardly anyone left to make any, or anyone who would bother to have them shipped out here. The whole system was all-but abandoned.

Senek got some steel tape and the remnants of an old exhaust line. With some ingenuity, he was able to mostly close up the leak. A few quick tests told him that it wouldn’t last forever, but it might just get him through the harvest.

Once the old ship was put back together, Senek climbed into the cockpit and started her up. The engines whined, and the gauge told him the reactor was at a quarter output.

Oh, well. I’ll replace the Vulc Crystal later. Glad I seeded extra for them.

The combine rose into the heavy, artificial atmosphere of Titan. Since the planet was so far from the Sun, the terraforming plants had to keep the air extra thick to trap as much heat as possible. This meant the sky was a uniform silvery grey; burnished at noon, tarnished at dawn and twilight. No stars or sun, not even the gas giant itself was visible from the surface.

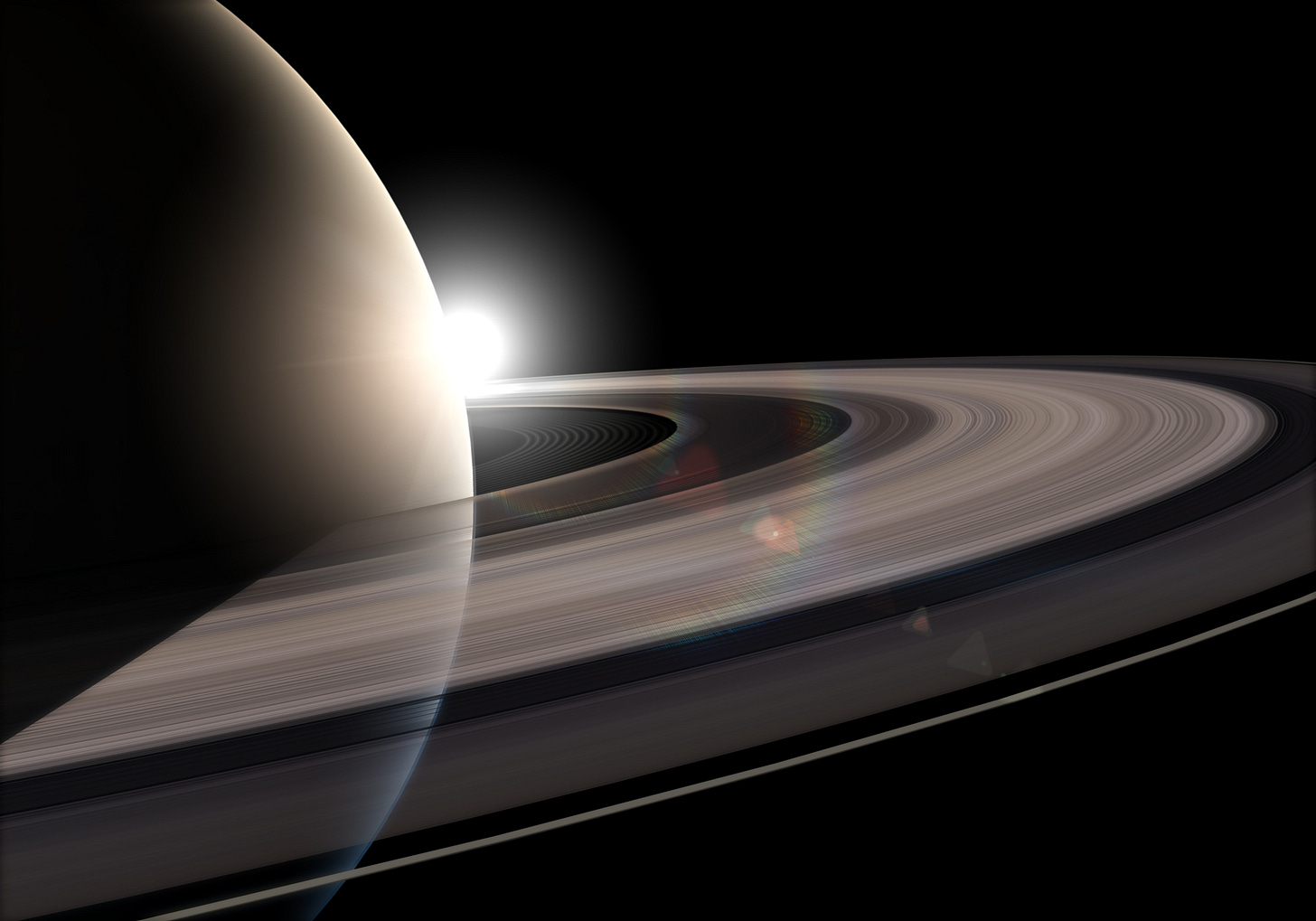

As he rose above the cloud layer, Senek saw the Sun (and even though mankind now dwelt in worlds orbiting a dozen other suns, this old lord and companion was still the Sun). He was only a little larger and brighter than the brightest stars around him, and considerably less so than Jupiter. The Sun’s light was now a dull, reddish, coppery color, and even from this distance, he looked tired, like a fire burned low and ready to flicker out.

When dealing with something as old as the Sun, you couldn’t peg an exact time of death. The philosophers said that it might be in an hour, might be in a hundred years. All they could say was that he was going to go Supernova, and astronomically speaking, it was going to be soon. Very soon.

Once this had been discovered, the arks had evacuated everyone from the old worlds – Earth, Venus, Mars, Europa, Io, and Titan – and taken them off to safety in the new systems. Every treasure and artifact had been taken off as well. Breeding populations of the animals and plants were taken, and even some of the buildings had been painstakingly deconstructed, transported, and rebuilt in new homes. Now the ancient cities stood all-but empty, and the only ones left were the stubborn or the crazy or the idealistic ones who chose to stay.

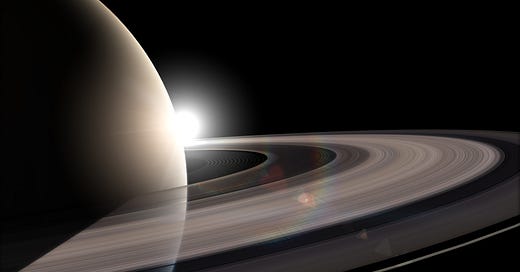

All this passed through Senek’s mind as he looked at the Sun, but it didn’t make much of an impression on him. The dying Sun was less important to him than the huge, bright world that dominated the sky before him: Saturn.

For Senek was a Ring Farmer, as had been his father, and his father before him, back into time immemorial, perhaps reaching all the way back to when mankind had first come to this old farmer of the sky and discovered his fruits.

In the Rings of Saturn, tens of billions of chunks of rock, ice, and vapor were hurled through space at thousands of miles an hour, pulled in one direction by the gravity of the planet, the other by powerful centrifugal forces. They were bombarded by unfiltered rays from the distant Sun, and intense radiation from Jupiter when he made his annual fly-by, as well as by rays from Saturn himself.

Under these conditions, the most fabulous and amazing geological transformations took place. Inside their rocky outer shells, the grains of the Rings contained gems and crystals unlike any in the known universe. Vulc Crystals, which were essential to cold fusion; Titan Jade, which was instrumental in creating hard-light; Chronite, which gave pulses of energy in exact proportion to the speed of its orbit and which had given birth to universal standard time, and a hundred others. These gems had powered technological revolutions, and even today were used in most reactors and other machines.

It had been discovered that this process could be, to some extent, controlled. By seeding the Rings with the proper elements, directing the proper forms of radiation onto them at regular intervals, and letting them spin through space for a year or more, most of the more valuable crystals could be grown to order. Thus the art of Ring Farming had been born; a delicate, complex, labor-intensive task, every bit as consuming as farming the land had been. Day after day, the Ring Farmers climbed into their combine ships and flew over their track of the Rings, checking for their seeds, irradiating them, or putting up shields to block incoming rays (an arduous process) as the case required. Then, at the end of the year, there came the harvest, when the gems were collected, cleaned, and prepared for shipment.

Collection took almost a full day at least. The cleaning and processing could take weeks, depending on how good the harvest was.

But there was one treasure that outshone all others: the Rhea Diamond. It was said that the Rhea were among the most beautiful objects to occur in nature, perfect gems that caught the light and reflected it outward in unimaginable colors and shapes, while shining with a lustrous glow of their own. They had no industrial properties, but their aesthetic qualities alone were enough to make them by far the most valuable objects that had ever been found on Saturn. Rich men would trade their entire fortunes for just one, and count themselves the winners in the bargain. It was more than simple decoration; men said there was something otherworldly, something sacred about those jewels. Those who possessed them often seemed to undergo dramatic changes of behavior; an unscrupulous banker would suddenly give away his whole fortune and run off to be a hermit. A bloodthirsty general would turn himself in for war crimes. Hard-bitten politicians would give up their careers and devote their lives to the arts.

Whatever the truth of the matter, everyone agreed that to posses a Rhea Diamond was to be rich in more than just material wealth. It was almost synonymous with being blessed.

Senek had never seen one, of course. Their composition was mysterious and seemed to include elements that had never been found anywhere else, so they were impossible to ‘seed’ for. Philosophers speculated that their base elements came from an object that entered the Solar System from far away, very early in its life, and despite all efforts it was impossible to create them artificially. Farmers had greedily sought them out, and even the vast Rings of Saturn could only hold so many of these unique gems. It had been over a millennium since anyone had found one. All the Rheas currently in existence were in museums or monasteries or a handful of private collections.

Every ring farmer still dreamed of finding a Rhea Diamond, of course, just like every sailor dreamed of mermaids or every hunter dreamed of discovering an as-yet unheard of beast. It was merely an idle fantasy, almost a myth. It didn’t affect daily business.

Senek’s track was on the outer edge of the B Ring; prime territory, which his family had worked their way up to over generations. He flew his ship low over the stream of ice, dust, and rock, all of it shining with the reflected light of the Sun. It was like skimming over a river of gold. As he flew low, the exhaust of his engines kicked up a spiraling wake of dust and rock, which turned into a spinning collage of gold, silver, and blue as it spun behind him, catching the light at different angles until it was drawn back into the Ring.

The time was that during the harvest you could see hundreds or thousands of such wakes, all across the Ring System. People on Earth and the other old worlds would train their telescopes at Saturn to watch his Rings flash different colors as the farmers plowed their fields.

Today, there were barely a dozen farmers out there, and Senek only knew that from his sensors.

He deployed his combine’s collecting arms. These were telescoping rods, two miles from end to end, trailing magnetic tendrils along the Ring surface to snag the ‘hooks’ that were attached to each chunk of rock and metal he had seeded at the beginning of the year. The arms would then draw them in and feed them into the combine’s hold.

Also being snagged were the raven drones; small probes released near the end of the growing season that were built to seek out and attach themselves to any naturally occurring crystals in the Rings. Though the Rhea Diamonds were all gone, Saturn was still a bountiful world, and sometimes the greatest treasures were found in what he had grown himself with no help from man.

Navigating the Rings was tricky, and had been even before the arthritis started to set into Senek’s hoary old hands. You had to fly slow enough to catch the hooks and drones, but not too slow so that the planet began to pull you in. You had to keep absolutely on the correct curve or you risked drifting off of your own track (the hooks and drones were matched to the ships, so that if you drifted onto someone else’s track, you wouldn’t pick up anything and would only lose your own harvest, or have to start over). You had to maintain the right altitude relative to the Ring itself, so that you didn’t go too high and the hooks wouldn’t catch or too low and you risked scattering or destroying the rocks themselves (not to mention your ship). It meant long hours of precise, intensive focus, of cramped muscles and sore eyes. The Rings were beautiful, of course, at least until you got on the far side of the planet and all was dark. There you could only navigate by relying on the instruments; if they malfunctioned, or if you hadn’t kept them properly calibrated, you might drift right off the Ring.

To make matters worse, Senek hadn’t even reached the dark side of the planet before he realized this would be an extremely bad harvest. His hold registered as barely half what it ought to have been at this stage, and the collection process seemed to be slowing down. Adjusting his speed and altitude didn’t help. Of course, he realized; his hooks were bad. There hadn’t been anyone to do the proper repairs on them in between growing seasons, and he’d had to fix them as best he could on his own. Likely the seeds – which he’d had trouble getting hold of – weren’t that good either. He’d have to figure on much of what he did bring in being unusable.

They had had bad harvests before, of course; years where Jupiter had put out more radiation than they’d expected, or where a stray meteor had scattered part of the Rings, or where, for whatever reason, things had just gone wrong. But this looked to be the worst he had ever had.

And then, he thought, even if he brought in a decent harvest, who would buy it? The other systems all had their own ring worlds now; any that had lacked one to begin with had been artificially supplied one by setting up a ring system around a suitable planet. He’d gotten almost no orders this year, down from the few he’d gotten the year before. And he likely wouldn’t be able to fulfill the ones he had. Heck, he’d be lucky if he brought in enough to keep his own ship in the sky.

Slowly, against all his stubborn efforts, the thought came into his mind at last: You can’t keep this up.

He was all-but broke, nearly ninety years old, with a ship on its last legs, farming an abandoned planet for a rotten harvest that no one wanted. His equipment was falling apart, and he almost certainly wouldn’t be able to afford any seeds for next year, even if anyone was still selling them.

Senek kept working. But he did it automatically, by sheer force of habit. He had farmed these Rings his whole life and now his body and mind just did it by instinct. But his heart was gone, and he felt as though he’d been suddenly hollowed out. The facts were undeniable; he didn’t even try to argue himself out of them. This would be his final harvest, even if he and the Sun lived for another twenty years.

But what then? The idea of life without farming was simply a blank to him. His wife was dead. His only living relatives lived lightyears away and hadn’t spoken to him in years. He had never left sight of Saturn, except for a few years in the navy when he was young. He didn’t know how to do anything but farm. And he had no money saved: nothing that would let him start over, even if he wanted to.

He completed his orbit. The cargo hold was barely a quarter full. Numbly, he turned his ship back to Titan. The really hard work was still to come.

The idea of stopping, of abandoning the harvest, never occurred to him, even as he looked beyond it into an absolute void. It was all-but pointless, but it was his job. He’d never left a job unfinished in his life. But he did it with a new sensation: a numb, hopeless kind of feeling. He had given his whole life to this work. His family had been ring farmers for time out of mind, and now that would have to come to an end. He thought he could have stood it better had the job been forcibly taken from him. Then he could have gotten angry, he could have had the consolation that he could have gone on, that he could have kept it up, if only…but not now. Now it was just fading away, like mist, or like a dying plant, and he could do nothing about it but watch.

Just like when his wife lay dying.

He landed the combine in the barn and drew the ramp from the cleaning machine over to the base of the cargo hold before opening it up. A tumble of rocks, ice, and crystals came spilling out, each one with either a mechanical tracker growing out of it or a small drone latched tight onto the stone.

Senek pulled on his helmet, picked up the guiding rod (they were still too cold to touch) and began feeding the stones one-by-one into the cleaner, where rapidly spinning abrasive panels tore off the outer rock layer to reveal the gems beneath.

It was late and he had had a long day. His eyes itched with tiredness and his old bones ached. But Senek didn’t want to go to sleep. He was afraid of the dreams that might come, of the thoughts that might assail him if he stopped working. He was afraid to contemplate the end of the harvest.

Hour after hour, nearly asleep on his feet, Senek fed the stones into the cleaner and sorted the resulting gems into their proper containers. It was as he suspected; most of the seeds hadn’t taken. He would be getting a decent amount of Vulc Crystals, a bit of Titan Jade, and some other valuable bits, but not nearly enough. Most of the rocks were duds: just compact masses of stone and minerals, absolutely no good to anyone.

The sky was beginning to glow silver again as he pulled the very last stone into the cleaner and leaned on his stick, breathing hard. A process that, in a good year, could take weeks was being finished over the course of a single night. Senek knew he needed sleep. He was old, and he had worked himself nearly to death. As soon as this one was finished, he would go to bed. Maybe, if he were lucky, he would never have to wake up.

The cleaner seemed to be taking a long time with this one. Senek groaned; he wanted to be done. The harvest was over, and he would have nothing to show for it: nothing to show for the labor of a lifetime. He just wanted to say he had stuck it out, had finished the job, but this damn rock was holding him up.

He stumbled over to the controls and pushed them up to maximum for a moment. This risked damaging the gem…no, couldn’t do that. There was no point, but still, it was bad practice. He eased the machine off. Fortunately, this seemed to have given it a grip at last, and the rocky crust began to fall away.

Senek was just about to nod off when a chip flew from the stone and a flash of brightest gold shone from within.

He blinked and stared, his heart leaping. It couldn’t be…

His weariness left him at once as the stone was cleared away and more and more of the brilliant gem shone forth. Now it seemed to take only an instant, and the cleaner was finished.

Senek shut the machine off, removed his helmet, and with trembling hands took the stone from machine.

He had never seen one, but there was nothing else if could possibly be: a Rhea Diamond. Probably the very last one in existence. For untold eons, it had spun around the old farmer of the sky. It had weathered thousands of years of treasure hunters, and had waited to be found, at the last, by this stubborn old man.

Senek held the glorious gem up to the rising light. It was warm, but not hot to the touch, and seemed to vibrate gently in his hand, more like a living thing than anything, and as it caught the light of the last sunrise it flashed and shone with many colors. Not just the colors he knew, but colors he had never seen before; perhaps colors that no one had ever seen. They were his own colors, from his own jewel.

“How about that, Aria?” he said. “Turns out it was a good harvest after all!”

Then, as he gazed at his treasure, the silver of the sky suddenly blazed white: blazed until all was light.

What Senek saw next, no man can say. What the remaining children of men saw from the far-off, newly settled worlds was that Senek and his harvest, together with Earth, Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, and all the other old, familiar worlds, were gone.